Nylon SLS vs FDM is one of the most common comparisons engineers face when choosing a 3D printing process for functional parts. One process yields flat, durable, production-ready parts. The other may struggle with warping, visible layers, or inconsistent strength. This gap is not a quality issue or a tuning mistake. It is the natural outcome of two fundamentally different manufacturing physics.

In the 3D printing world, material choice matters, but process selection defines performance. Nylon makes this especially clear. Understanding how SLS and FDM interact with nylon at a physical level is the difference between predictable results and repeated trial-and-error.

Nylon as an Engineering Polymer

Nylon is widely used because it balances strength, toughness, fatigue resistance, and chemical stability. It performs well in moving assemblies, load-bearing components, and functional housings. At the same time, nylon is hygroscopic and exhibits relatively high thermal shrinkage. These characteristics do not make nylon difficult, but they make it process-sensitive.

SLS and FDM manage heat, bonding, and cooling in very different ways. As a result, the same polymer behaves like two different materials depending on how it is formed.

Process Physics: Why SLS and FDM Create Different Microstructures

FDM prints nylon as a molten filament extruded layer by layer into open air. Each layer must bond thermally to the one below it while cooling immediately after deposition. This creates a laminated structure in which bonding strength depends on temperature control, moisture content, and timing. The microstructure is directional by nature, which leads to anisotropic mechanical properties.

SLS forms nylon parts by selectively sintering powder with a laser inside a heated chamber. The surrounding powder supports the part and maintains a stable thermal environment. Bonding occurs throughout the part volume rather than at discrete layer interfaces. The result is a more uniform internal structure with mechanical properties that are closer to isotropic.

This difference in microstructure is the root cause of most performance gaps between SLS and FDM nylon parts.

Warping and Dimensional Stability

Warping is one of the most common failure modes for nylon, and it highlights the contrast between the two processes.

In FDM, nylon cools rapidly in open air. Large flat surfaces are especially vulnerable because thermal shrinkage accumulates in a single plane. Internal stresses concentrate at corners and edges, often lifting parts from the build plate or introducing curvature across the surface. Parameter adjustments can reduce this behavior, but they rarely eliminate it for large or thin geometries.

In SLS, the powder bed acts as both mechanical support and thermal buffer. The entire build cools gradually and uniformly inside the chamber. Shrinkage still occurs, but internal stresses are far more evenly distributed. As a result, SLS nylon parts maintain dimensional accuracy and flatness even at larger scales.

For designs where geometry must remain true after printing, this difference alone often determines process choice.

Mechanical Performance and Surface Characteristics

FDM nylon parts typically exhibit good strength within the print plane but reduced strength across layers. This directional behavior is acceptable for fixtures, jigs, and brackets where loads are well understood. Surface finish reflects the layer-by-layer process, with visible texture that may require post-processing for cosmetic or mating surfaces.

SLS nylon parts display more consistent mechanical behavior in all directions. Surface finish is matte and uniform, closer to injection-molded plastic than to layered deposition. While not glossy, it is predictable and well suited to functional interfaces, snap fits, and assemblies.

The distinction is not about absolute strength, but about reliability and repeatability. When a part must perform the same way regardless of orientation or loading direction, SLS provides a narrower performance window.

Design Freedom and Geometric Constraints

Design intent translates differently through each process. FDM requires support structures, minimum wall thicknesses tied to nozzle diameter, and careful planning for overhangs. Complex internal channels or lattice structures are often impractical or impossible without significant compromise.

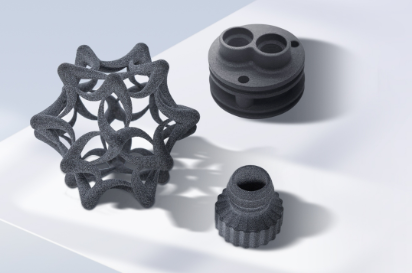

SLS removes most of these constraints. Parts are supported by surrounding powder, enabling thin walls, enclosed features, lattice structures, and organic geometries without added supports. This design freedom is not cosmetic. It allows engineers to reduce weight, integrate functions, and optimize structures without manufacturing penalties.

When geometry complexity increases, SLS shifts from being an advantage to being a necessity.

Production Context and Cost Behavior

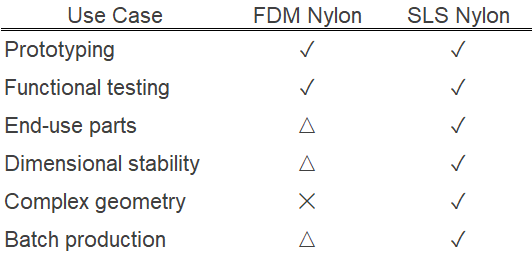

FDM is well suited for rapid iteration, low-volume prototyping, and functional testing. Setup costs are low, turnaround is fast, and design changes are inexpensive. For development environments, this flexibility is valuable.

SLS becomes more efficient as part complexity and batch size increase. Multiple parts can be nested in a single build without added setup effort. For low-to-medium volume production, SLS often achieves a lower cost per functional part when post-processing, reprints, and dimensional corrections are considered.

Choosing between SLS and FDM is therefore not a question of which is better, but which aligns with the stage and intent of the project.

When Each Process Makes Sense

FDM nylon is appropriate when the goal is iteration, functional validation, or tooling where directional strength is acceptable and minor deformation can be tolerated. It supports fast learning cycles and cost-effective experimentation.

SLS nylon is the better choice when parts are expected to function in assemblies, experience real loads, or ship as end-use components. Its dimensional stability, isotropic strength, and design freedom reduce downstream risk and variability.

In practice, many successful workflows use both. FDM supports early development, while SLS carries the design into functional deployment.

Conclusion

Nylon does not fail in 3D printing. Mismatch does. When nylon performs poorly, the cause is often not the polymer but the process chosen to shape it.

SLS and FDM represent two distinct manufacturing realities. Understanding their physics allows engineers to predict outcomes rather than troubleshoot surprises. The most reliable nylon parts are produced when material behavior, process characteristics, and design intent are aligned from the start.

The difference between a warped prototype and a production-ready component is rarely a parameter tweak. It is a process decision.