Nylon (polyamide, PA) is one of the most widely used engineering materials in 3D printing—and also one of the most misunderstood. Its strength-to-weight ratio, wear resistance, and fatigue performance make it an obvious choice for functional parts, structural components, and low-volume end-use production.

At the same time, nylon is responsible for more failed prints and frustrated first attempts than almost any other material. Warping, moisture sensitivity, dimensional drift, and inconsistent surface quality often lead teams to abandon it early.

The issue, however, isn’t that nylon is unsuitable for 3D printing.

If that were true, companies like Porsche and Adidas would not be using it in production environments.

At Hyperlab3D, we see nylon as a high-performance material that demands engineering discipline. It doesn’t tolerate shortcuts—but when handled correctly, it delivers results that few plastics can match.

Moisture Sensitivity: Where Most Nylon Problems Start

Nylon is inherently hygroscopic. It absorbs moisture quickly from the surrounding environment, and even small amounts of residual humidity can have a noticeable impact on print quality. During printing, trapped moisture vaporizes, weakening layer adhesion and causing rough surfaces, internal voids, and reduced mechanical strength.

In many failed nylon projects, print settings are blamed when the real issue is material condition. Industrial-grade nylon printing requires more than casual drying. It calls for defined drying procedures, controlled storage, and consistency from material preparation through final build.

At Hyperlab3D, material conditioning is treated as part of the engineering process—not a last-minute adjustment. Stable results begin long before the printer starts.

Warping and Deformation: Nylon’s Most Common Structural Risk

Compared to materials like PLA or ABS, nylon undergoes greater thermal contraction as it cools. Without proper temperature control and design consideration, warping and deformation are difficult to avoid. Large parts may lift at the corners, thin-walled structures can twist, and tight-tolerance components often reveal problems only during assembly.

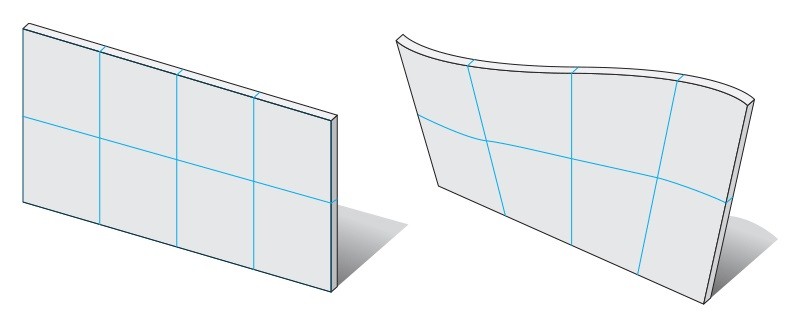

Large flat geometries are particularly prone to warping when printed in nylon. This behavior is driven less by insufficient material strength and more by nylon’s relatively high thermal shrinkage during cooling. In large, continuous planar areas, shrinkage occurs in a uniform direction, causing internal stresses to accumulate rather than dissipate. Because flat structures inherently offer low bending stiffness, even moderate thermal stress can result in visible deformation such as corner lift or overall curvature. Uneven cooling across large surfaces further amplifies this effect, making distortion difficult to control through process parameters alone. For this reason, large uninterrupted flat areas are generally avoided in nylon part design whenever possible.

Warping in nylon isn’t solved by a single parameter change. Effective control requires a system-level approach that includes environmental temperature stability, optimized part orientation, geometry-aware wall thickness design, and calibrated shrinkage compensation specific to each nylon formulation.

At Hyperlab3D, nylon parts are never treated as generic prints. Manufacturing constraints are evaluated early in the design phase, allowing deformation risks to be addressed while changes are still inexpensive.

Using Material Selection to Reduce Warping

Process control and design optimization are critical—but material choice itself can significantly influence warping behavior.

Carbon fiber reinforced nylon, such as PA-CF, incorporates short carbon fibers into the nylon matrix. This reinforcement increases stiffness and reduces uneven thermal shrinkage, resulting in improved dimensional stability during printing.

Beyond strength gains, the reduced tendency to warp makes PA-CF especially well suited for large components, thin-walled geometries, and lightweight structural parts where dimensional accuracy is critical. In many cases, it delivers far more predictable results than unfilled nylon.

PA12 vs. PA6-GF vs. PA-CF: An Engineering-Driven Selection Approach

From an engineering perspective, PA12, PA6-GF, and PA-CF are not competing materials—they are tools designed for different performance priorities.

PA12 is one of the most established engineering nylons, particularly in SLS processes. Its key advantage is balance: good mechanical strength, excellent dimensional consistency, and reliable repeatability. PA12 is a strong choice for complex geometries, functional assemblies, and production runs where predictability matters.

PA6-GF (glass fiber reinforced nylon) emphasizes stiffness and thermal resistance. The addition of glass fibers significantly increases modulus and heat deflection temperature, making it suitable for load-bearing components. However, this comes at the cost of increased sensitivity to warping and more demanding process control.

PA-CF strikes a more favorable balance between stiffness and dimensional stability. Carbon fiber reinforcement improves strength-to-weight performance while reducing deformation during printing. As a result, PA-CF is often the preferred option for lightweight structural parts, larger components, and applications with tight deformation tolerances.

In practice, selecting the right nylon has less to do with maximizing datasheet values and more to do with matching material behavior to functional requirements.

Why High-End Industrial Applications Still Rely on Nylon

If nylon were only suitable for prototyping, it would not appear in production-grade workflows.

Porsche uses SLS-printed PA12 components for certified spare parts in classic vehicles. These are not visual samples—they are validated, install-ready components designed for long-term use, enabling on-demand manufacturing without the burden of tooling or inventory.

UNYQ applies SLS nylon to highly customized medical and wearable products. Nylon’s toughness, combined with the design freedom of additive manufacturing, allows each product to be tailored to the individual without compromising durability.

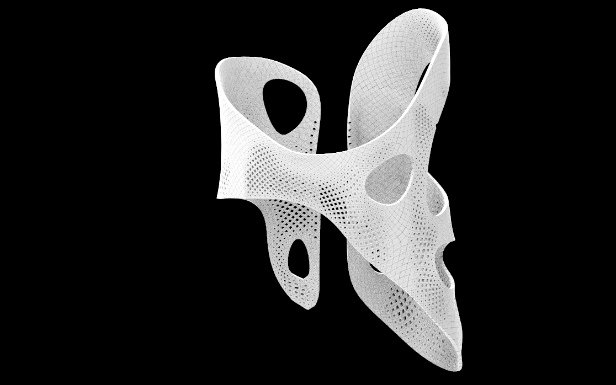

Adidas uses 3D-printed nylon lattice structures in performance footwear midsoles. By controlling geometry and material response, designers can tune cushioning, rebound, and fatigue life—demonstrating nylon’s role not just as a material, but as a structural performance system.

Across industries, nylon is not a compromise. It is a deliberate engineering choice.

The Real Barrier Isn’t Nylon—It’s Process Maturity

The mixed reputation of nylon in 3D printing comes down to one thing: engineering maturity. Nylon does not forgive poor preparation, but it consistently rewards disciplined workflows with production-ready performance.

At Hyperlab3D, nylon is never treated as a simple material option. It is part of an integrated engineering decision—covering material conditioning, design intent, process control, and post-processing strategy.

The real question isn’t whether nylon is worth using.

It’s whether the workflow is mature enough to use it properly.